By Alan MacFarlane, Deputy MoAS Guild Liaison

Iron as a metal was important to European society during the early Scientific Revolution (16th century). The metal had many uses including as tools, implements of warfare, architecture, and more. The knowledge at the time of iron ores, mining, smelting, chemistry – and even crystallography – were surprisingly advanced. Iron was given a detailed investigation by the keen minds of the time. Many individual engineers, scientists, and alchemists collected observations, data, and performed experiments. Specific information was determined and cataloged in a way not before seen in Europe.

Mine engineering and mining methods were given scrutiny at this time. Georgius Agricola’s De Re Metallica (1556) contains a thorough treatment of mine engineering. His book includes a plethora of woodcuts and illustrations of mining methods. The life of a miner was also described thusly by him, “Mining is a perilous operation to pursue; because the miners are often killed by the pestilential air they breathe; sometimes their lungs rot away; sometimes the men perish by being crushed by masses of rock; or falling from ladders.”

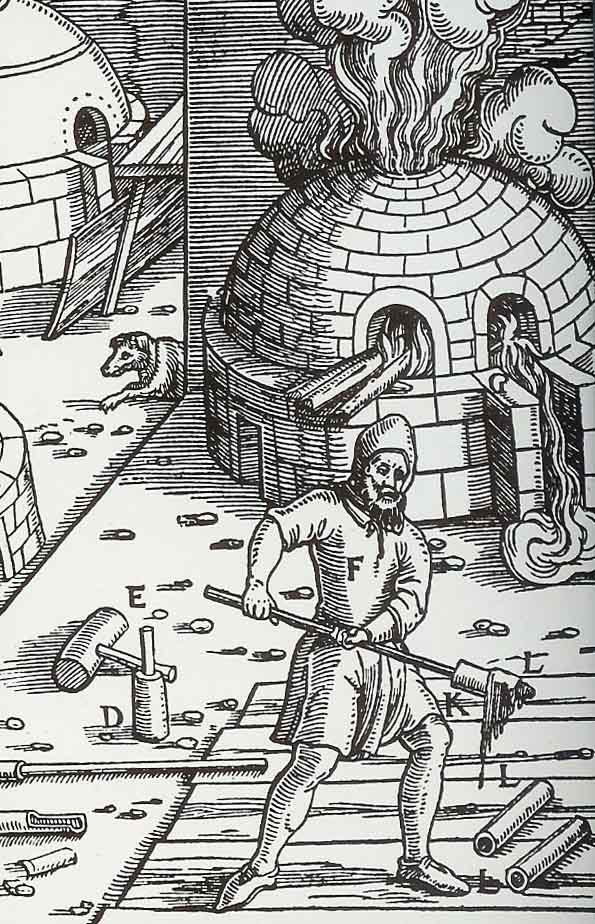

Iron ore processing was both recorded and then advanced at this point in history. Both Agricola and Vannocio Biringuccio mention ore beneficiation processes. Specifically mentioned are ore roasting, crushing, sorting and washing. Agricola also experimented with using natural magnets such as lodestone to perform simple magnetic separations of iron ore. He also cataloged many illustrations of ore crushing equipment. Both mechanical and water powered setups are shown in his book. Agricola was also aware of the environmental consequences of mining and ore processing. “Fields are devastated by mining operations- beasts exterminated, waters poisoned by the washings.”

Knowledge of the occurrence, type, and quality of iron ores in Europe received much attention during the early Scientific Revolution. Several authors mention the occurrence of iron ores. Georgius Agricola discusses this in his De Re Metallica. Vannocio Biringuccio states in the Pirotechnica (1540), in reference to iron ore: “Nature produces iron abundantly in many regions of the world.” He also mentions the occurrence of iron ores in mountainous areas as well as a lengthy discussion of known Italian ore sources.

The quality of these ores were also studied. Agricola studied the orientations of ore seams, quality, and type. Biringuccio gives us a very accurate accounting of the measurement of the strike and dip (orientation) of vein formations. The Pirotechnica mentions red earth as an indicator of the presence of iron ore at a site. Varying descriptions of differing types of iron ore, their appearance, and their suitability for refinement are recorded in the book as well.

The art of iron smelting and alloying occupied many scholars of the time. Two types of furnace are mentioned by Biringuccio in his book. Both a blast furnace and a bloomery forge are mentioned. Indeed, Agricola’s aforementioned illustrations also include drawings of a blast furnace as well as detailed plans for their construction. He discusses sites for such operations as being best suited near a method of transport – by land or water.

Biringuccio was well aware of steel alloys and impurities. These factored into knowledge of tempering processes. Giovanni Battista Della Porta gave detailed descriptions of quenching processes in his work, Magiae Naturalis Libri Viginti (1589). Among them were using substances such as vinegar, urine, ram’s blood, spring water, crushed snails, oil and a host of others. A water quenching method is mentioned by both Biringuccio and Agricola as well.

The chemical properties of iron began to be cataloged and studied in earnest at this time. Flame test assays of iron are mentioned by Agricola and Biringuccio both. A blue colored flame and “infernal odor” to test for sulfur was mentioned. These sorts of investigations would help lead later authors such as Pierre Clement Gignon and Jousse Mathurin along their own paths of learning.

In conclusion, the science and understanding of iron was clearly advanced during the early Scientific Revolution by a handful of authors; and the many others who may not have written. Societies with high quality iron had social, military, and economic advantages. Iron was vital to the advancement of European society at this time. This advancing science and the removal of myths around the metal served to propel society forward.