by Helena Kassandreia, MKA Jessica Gebhard, Shire of Roxbury Mill

Introduction

In the pre-pocket era, purses were a common means of carrying around money and small, precious items. Depending on the wealth and whims of the owner, they could be anything from simple and utilitarian to extravagantly ornamented, up to and including the incorporation of precious silk and metal threads.

For the purposes of curiosity, and because I hadn’t tried reproducing a specific item from a manuscript before, I wanted to try making the bag shown in Libro de los Juegos, a Spanish translation of an Arabic text on games that was commissioned by Alfonso X at the end of the 13th century. The manuscript shows two figures playing chess; below them hangs a white bag with a design of red lines and blue dots along the bottom edge. There is also a line of red dots along the top edge, and the entire bottom edge is fringed.

FIGURE 1 FOLIO 40 RECTO, LIBRO DE LOS JUEGOS. EL ESCORIAL, SPAIN. (SOURCE: KELLY)

Spain and the Silk Road

Though the Silk Road is usually discussed as an east-to-west trip, flowing from China and neighboring areas to Europe, some enterprising silkworm traders made an early end-run around the Iberian peninsula to establish sericulture in Spain at the beginning of the Medieval period.

Historical records and extant evidence shows that the silk industry arrived in Spain in the early eighth century, as part of the Arab conquest of southern Iberia. By the tenth century surviving documents trace the cultivation of mulberry trees, the rearing of silkworms, the unwinding of cocoons, and silk weaving in Andalusia. Additionally, records of large numbers of silk fabrics changing hands imply a large workshop and attendant workforce (Jacoby). The prominence of various centers of Spanish sericulture and silk manufacture rose and fell through the decades and centuries, but Jacoby traces a number of high-value Spanish silk fabrics and silken items though the mid-thirteenth century, some of which were traced as far as Italy and England. Accordingly, it is entirely plausible for this purse to incorporate both silk fabric and silk thread, which in-period might have been imported or of domestic manufacture.

Construction

The body of the purse is a single rectangular piece of embroidered silk, with the embroidery done along the lower edge of one long side. This is then folded lengthwise and both the side and bottom seams stitched closed. This is the same construction as the pouch in Figure 3.

The Embroidery

Try as I might, I was unable to locate extant Adulusian purses from the era[1], so I was forced to travel farther afield for extant exemplars, and landed on a pair of Byzantine 9-12th century reliquaries, currently housed in Switzerland, both of which have geometric (or nearly so) figures, as the manuscript does. Though this is a mildly roundabout connection, it is not an unfounded one; Jacoby notes that Byzantine silk was making its way to Spain as early as the 940s, and Kelly adds that in 13th century Paris, such silk and precious-metal embroidered purses were known as “aumônières sarrazinoises”: “Saracen alms purses.” While the exact meaning of that name is unclear, one of the possibilities is that the “Saracen” purses were of local make in imitation of those seen in “Saracen” lands. If this is the case, it is not implausible that similar imitations were made just over the border in Spain. Though not ideal, it’s enough to start with, and a not implausible reason to use silk thread over a silk ground, as the Byzantine purses do and which I had never tried before.

I used blue and red filament silk threads and white silk fabric (donated for the purpose by Ollamh Lanea inghean Uí Chiaragáin), and rapidly discovered that while filament silk does look very nice, it is also very annoying to work with, especially in winter, where it catches upon every single dry patch of skin available. I also had a long false start using an embroidery hoop; the final piece was made without the use of a hoop, but with a linen backing to prevent pulling. The stitches themselves are split stitches, a common stitch for silk that allows long lines to “flow”.

The eyelets are matching red silk, as suggested by the manuscript. They were made with an awl, as was period practice; this pushes the fabric aside, rather than cutting it, which makes a much stronger eyelet.

The Strap

The purse’s strap is tablet-woven mercerized cotton, though in a perfect world it would have been silk as well; however, I didn’t have enough white silk for both the strap and the fringe, and I thought it would have looked odd if the strap and fringe didn’t match. The strap is tablet-woven and is attached along the sides of the purse; compare Figures 2 and 3, both of which also have tablet-woven straps that descend along the sides. I considered for some time whether the circles at the apex of the strap in the manuscript indicates loops, but decided that the length of strap required would be unlikely for practical reasons.

The Tassels

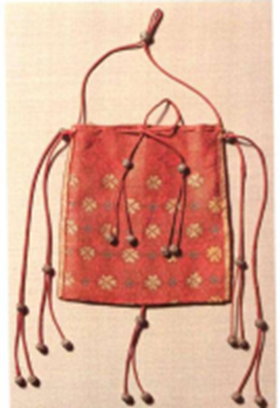

The fringe is also mercerized cotton, as noted above. While most extant purses have only a few tassels or knots, a few have the profusion of tasseled fringe seen in the manuscript (compare several of the examples seen in Figure 4).

The Eyelets and Drawstring

While there is not a clear drawstring in the manuscript, most extant exemplars from the period use drawstrings, and the row of red along the top edge of the purse certainly suggests red eyelets to match the red lines. Mine are the same silk as the embroidery and made using an awl.

While the extant examples have tablet-woven drawstrings, mine is lucetted. I had originally hoped to have tablet-woven drawstrings, but my eyelets turned out much smaller than planned, and lucet-cord (mercerized cotton again) was the best historically-plausible alternative. The manuscript doesn’t show how the cords are ended, so I chose to end them with tassels, as seen in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Lessons Learned

As noted in the section on embroidery, I had a few false starts, mostly focused on tensioning; I’m still not altogether happy with the degree of puckering on the final piece. I was also pretty sure I could get my pencil marks out of the silk and was wrong; they can still be seen in some places. Finally, despite careful measuring, the eyelets were not spaced out as evenly as I would have wanted. Overall, I’m happy with each individual part of this project, but not altogether delighted with the complete item. File it under “Learning Experience”!

FIGURE 2 BYZANTINE RELIC POUCH, 10TH OR 11TH C. ST. MICHAEL, BEROMUNESTER, SWITZERLAND. (SOURCE: KELLY)

FIGURE 3 BYZANTINE RELIC POUCH, 9TH C. ST MICHAEL, BEROMUNSTER, SWIZTERLAND. (SOURCE: KELLY)

FIGURE 4 GERMAN RELIQUARIES, 14TH C. LIEBFRAUENKIRCHE OF VALERIA, SWITZERLAND. (SOURCE: KELLY)

Sources

Historical Needlework Resources. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://medieval.webcon.net.au/index.html

Jacoby, David. (2017). The production and diffusion of Andalusi silk and silk textiles, mid eighth to mid-thirteenth century. In: The Chasuble of Thomas Becket. A biography p. 142- 151. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.academia.edu/35633421/The_production_of_silk_Andalusia.

Kelly, T. D. (n.d.). Aumônières, otherwise known as alms purses [web log]. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://cottesimple.com/articles/aumonieres/ .

UNESCO. Silk Roads Programme: Spain. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/countries-alongside-silk-road-routes/spain .

[1] If you have a line on this, please let me know! gebhard.jessica@gmail.com