By Mistress Deirdre O’Siodhachain

This article originally appeared in The Oak #20. This article has been edited and updated by the author. As the author, I would like to note that a lot of work has been done by others in this area since the article first saw print. While my focus then and now has been on elevating understanding of the qualities of a proper legal document with its subtle adornments, there are examples of legal documents decorated with gilding and illumination that were intended as presentation pieces as much as legal records. The updated version of this article includes some of those references. There is room for a great deal more research on the topic.

In the 21st century, we have a variety of ways to determine if a legal document is authentic and to secure it against tampering or forgery. What of the Middle Ages and Renaissance? When every document was unique, how could its integrity and validity be ensured? Period clerks had a variety of techniques and conventions to achieve this.

I identify six major characteristics that were commonly used in creating a secure legal document during that time: inherent value, seals and marks, formulaic language, text positioning, flourishes and decoration, and indenture. A legal document might use a few or all of these.

Inherent Value

In our time, paper is cheap and readily available, and thus reproduction of documents is as well. The photocopier is ubiquitous and inexpensive to use. There are official archives where copies of documents may be registered and deposited. Virtually every household retains files of multiple legal documents vital to its functioning (IRS forms, birth certificates, leases or mortgage papers, etc.). Most of us now have both paper and electronic archives of PDFs to keep track of the important items. The ability to retain records in multiple places means the loss of valuable information is rare, and the contents of legal documents difficult to dispute or forge.

Compare this to the Middle Ages, when a legal document of any sort was a relative rarity. Outside of tax records (which were kept by the authorities, not individuals), an entire life could easily pass without the registration of a birth or marriage or any sort of contract. Legal documents were largely a thing for the upper classes who were far more likely to have property that required more than a verbal agreement for its ownership, administration, change of social status, and/or terms of service.

All medieval documents represent an investment in time and materials. All materials were handmade from potentially uncertain supplies that were not cheap or all that common.

Vellum and parchment are time-consuming to make. As end products of mainly herd animals, their creation meant that an animal had to be taken out of production (for milk or wool and/or as breeding stock) and was no longer a source of wealth generation. The best vellum comes from younger animals, since those hides will have the fewest blemishes. The amount of resulting vellum will also be less because of the smaller size of the source. As a result, good quality writing surfaces could be extremely costly to produce.

The best inks – the most permanent and darkest – had a primary ingredient of oak galls (as a source of tannin). Such galls are fairly common but had to be sought out, harvested, and processed. This took time, manufacturing resources, and knowledge.

Quill pens came from a common source of any bird that produced long, strong feathers. Notably geese were one major source. While the feather itself was not difficult to obtain, skill and a penknife were involved in preparing it as a writing instrument. This took practice. The quill itself had a short productive life.

The ability to read and write was a considerable accomplishment in itself, and the products of these skills were held in esteem. The composition of a legal document also required a background of legal training both religious and secular. It is worth noting that because the vast majority of clerks were trained at or associated with a religious center. Members of the legal profession were usually holders of minor religious offices although they did not have to be monks or priests. In any case, legal documents had an aura of sanctity. These were attested to by oaths to God as well as lay authorities.

Thus, the skills and/or materials needed to create a single document were inherently valuable and recognized as such. They could not easily or casually be duplicated and took time to acquire.

Seals and Marks

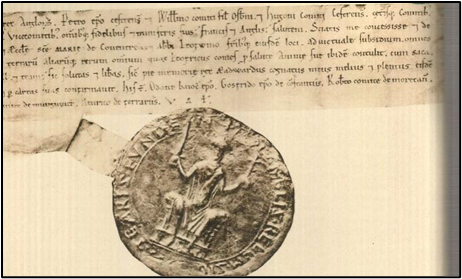

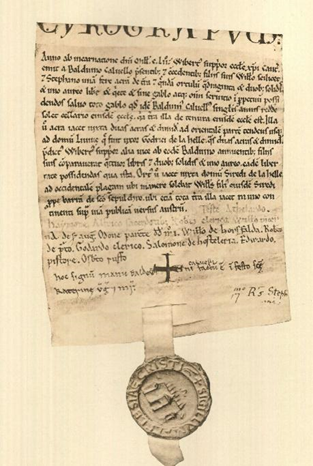

Figure 1 Example of document with multiple seals attached (Henry II, 1185)

The personal signature or mark (or “sign manual”) was not the main way to prove a document’s validity until the post-medieval period (more on signatures below). The wax seal(s) attached to the document had greater importance and was the main means of validating legal agreements. Each seal matrix was unique and a carefully guarded property.

Wax seals were attached to documents in a variety of ways, and those that were more tamper-proof would have been given greater credence if challenged.

A seal is formed by putting a quantity of warm beeswax in a mold and impressing an image from a seal matrix on it. The beeswax was either left in its natural yellow-brown color, or dyed red or green. Seals can be one- or two-sided with two-sided being the more secure. To attach a seal, a length of vellum, cloth ribbon, or braided string is integrated into the seal by laying it between two layers of wax before impression. Note that secular seals were generally round in shape and those of religious houses or persons were navette-shaped (oval with pointed ends).

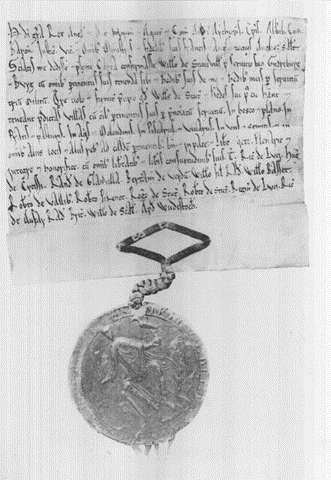

Figure 2 Example of tongue seal attachment (William I, 1170?)

The first tamper-proof type of seal attachment is when a “tongue” of vellum is used. A sheet of vellum has the legal text written on it. Next, a long cut is made along the bottom or side of the document that does not fully detach the length from the whole. The resulting “tongue” is then integrated into the seal as noted above; sometimes the tongue was tied into a knot to improve security, because then the tongue cannot be pulled out without breaking the seal. The seal cannot be then used to forge another document.

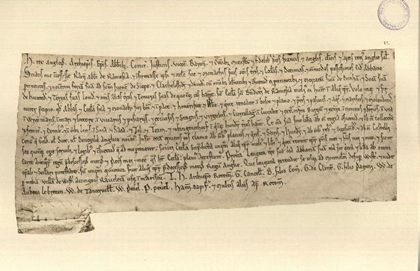

Figure 3 Example of threaded seal attachment (Henry II, prior to 1166)

Second best is the use of a threaded tag. A document is folded along the bottom to create a stronger platform to attach the seal. A slip of vellum, ribbon, or string is then threaded through a slit in the doubled vellum. The tag is placed in the wax before the seal is impressed.

Figure 4 Braided string seal attachment

Alternatively, the seal with an embedded tag was sometimes made separately and then later sewn on to the doubled vellum. This type of attachment was often used when multiple seals were added from different chanceries.

The third type of seal attachment is when a seal is pressed directly on to a document, similar to that with which we are familiar in envelope enclosures. This was rare in earlier documents and more likely used in sealing secure communications, not legal documents.

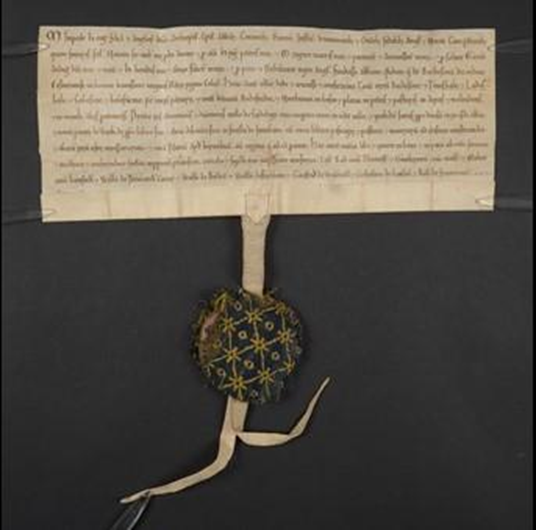

Figure 5 Embroidered seal bag on charter of Empress Matilda, 1128?

Wax seals are fragile, and great care was taken to preserve them; a document without a seal was open to legal challenge. They were frequently wrapped in cloth or vellum to try to protect them from breakage. If broken, the pieces were secured in a wrapping to keep them together with the document.

The vellum or parchment might be repaired to ensure that the seal remained attached to the document. This was not always successful.

Figure 6 Mark of the cross to witness presence of named signatories

The practice of signing a document to attest to its contents was used, but since many people could not write their own names, it was not consistently done. Use of personal marks was common. When a name was signed, it was quite common to accompany it by adding a cross mark as a form of swearing to the actual presence of the signatory whether he/she signed personally.

Formulaic Language

Legal documents had highly conventional language, which added to the sense of the validity of the document. English royal documents almost invariably open with the same phrase, “We, <Insert King’s Name Here>, King of England” followed by a list of legal dignitaries. Variations in language suggested that the writer did not know the correct legal forms. This could cast the legitimacy of the document into question. In addition, lack of variation in text helped to prevent errors and misunderstanding in interpreting the text.

Documents also used a lot of abbreviations. This was partly to save space and partly because the formulas were so well known it was not necessary to spell everything out. The writers were trained in the same type of schools and spoke a common language, and the courts would know this. Compare the creation document of John de Bermyngeham in the reign of Edward II (1307-1327) with that of John Nevyll de Montague in the reign of Edward IV (1461-1470, 1471-1483):

- Edwardus, Dei gratia Rex Anglié. Dominus Hibernié, et Dux Aquitanié, archiepiscopis, espicopis, abbatibus, prioribus, comitibus, baronibus, justicaiariis, vicecomitbus, prepositis, ministris et omnibus ballvis et fidelibus suis, Salutem. (Formula Book of English Official Historical Documents, p. 32)

- Rex omnibus ad quos, etc. Salutem. (Formula Book of English Official Historical Documents, p. 63)

Also compare the evolution of language between the creation charters or letters patent – these are not interchangeable terms although the distinctions are not always obvious – for earls in 1140, 1319, 1464, and 1553 from Stephen, Edward II, Henry V, and Mary I respectively. The translations are used for clarity.

- Stephen, King of the English, to His Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots, Earls, Judges, Barons and Sheriffs and all his Ministers and faithful subjects French and English, of the whole of England, greeting. Know that I have made Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of the County of Essex, hereditarily, wherefore I will and grant and firmly direct that he and his heirs after him by hereditary right shall hold of me and my heirs well and in peace and as freely and honourably as other Earls of my land hold the earldoms whence they are Earls with all dignities and liberties and customs with which my other Earls hold.

In the presence of which men are the companions of my perfect dignity more worthy, or more freely bear witnesses. William Ypres and Henry of Essex, and his son John, Robert son of Walter and Robert Newcastle and Mainfeninus Briton and Turgisio of Abrincis and William St. Clare and William of Dammartin and Richard son of Ursi and William of Eu and Richard son of Osbert and Ralph de Worcester and William son of Aluric, and William son of Arnold. at Westminster . (Peerage Law in England, p. 241).

- Edward, by the grace of God, king of England, lord of Ireland, and duke of the Aquitaine, to our faithful archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors, counts, barons, justiciars, viscounts, reeves, serjeants, and all bailiffs, Salutation. You may know the good and laudable service that our beloved and faithful John of Birmingham offered us lately against the rebellion in Ireland. During that conflict both John and those faithful during this rebellion among whom that same John was captain killed both Edward the Bruce, our enemy and rebel, who made himself king of Ireland, disinheriting us, crowning himself, as well as those who followed him from the start as it pleases the Lord. And also for the good service that the same John expended to us and our successors in the future, among the prelates, counts, barons, and other nobles of our kingdom in this present parliament we give, we grant and we confirm by this our charter to the noble John 20 pounds given annually for the County of Louth securing equal portions at Easter and Saint Michaels’ Day, we, having spoken, place that John in command of the court of Louth of that County. To have and to hold of this John and his male heirs of his body born legitimate under the name and honor of the Count of the aforementioned court for us and our heirs for the feudal service of four shares of one knight forever. And if this John dies without male heir legitimately born of his body, then the aforementioned 20 pounds annually returns to us and our heirs and returns whole. Thus it is spoken. By this witness given by our hand at York on the twelfth day of May in the twelfth year of our reign. (A Formula Book of English Official Historical Documents, Part I, p. 32, translation from Latin original by Gerald O’Leary)

- The King [Henry V] to the same [Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots, Priors, Dukes, Earls, Barons, Justices, Sheriffs, Reeves, ministers and all his bailiffs and trusty people], greeting. It is evident that the price is glorious, and the commonwealth under him consequently happy, who is encompassed the aid of many noblemen, and especially of those who are powerful in action. For as Heaven is made bright and shining with stars, so Kings and realms are refulgent with the light of dignities; not that man is changed by honours, but because he is made more virtuous who through is own famous merits is raised up to honours and elevated to the highest dignities; for what man will find fault with the opinion of one whom he knows to be chosen to the summit of dignity by reason of the excellence of his merits? Revolving these things therefore in the study of the Royal highness, and considering that the reward of merits proceeds from a justly ruling government; and having regard to the assiduity, prudence and laudable conduct which we perceive to flourish in our illustrious and renowned Cousin Henry de Percy, and therefore willing very amply to honour his person according to the renown of his race and the merits of his manners, so that by his power and prudence the Royal sceptre may be supported, we have given to the same Henry the name and honour of Earl, and we do prefer him as Earl of Northumberland, and by the girding of the sword we do invest him with the same name and honour: To have and to hold the same name and honour of Earl of Northumberland to him and his heirs for ever. And to the end that the same Earl according to the worthiness and nobility of the said name may be able to the more honourably to behave himself, we have given and granted and by this our charter have confirmed for us and our heirs to the aforesaid Earl under the name of Earl of Northumberland twenty pounds, to be received and had to him and his heirs aforesaid every year out of the issues of the same County by the hands of the Sheriff of that County who for the time shall be at the feasts of Saint Michael and Easter by equal portions for ever. Wherefore we will and firmly command for us and our heirs that the aforesaid Henry shall have and hold the name and honour of Earl of Northumberland, and shall have and receive the said twenty pounds yearly under the name of Earl of Northumberland out of the issues and profits of the County aforesaid to him and his heirs for ever as it is aforesaid. These being witnesses (etc.) Given by our hand at Westminster, the 16the day of March. By the King himself. (Peerage Law of England, p. 272-3)

- Mary, by the grace of God, etc., to archbishops, bishops, etc., greeting. Of our special grace and certain knowledge and mere motive have erected, preferred and created the said Edward as Earl of Devon, and by these presents erect, prefer and create to him the name, status, style, title, honour and dignity of Earl of Devon, with all and singular the preeminences, honours and other things whatsoever of such status of Earl of Devon appertaining, we give and concede by these presents to him, the said Edward, of the same style, title, honour and dignity by the girding of a sword we have marked, invested and really ennobled, and a cap of honour and dignity, also a circle of gold on his head we place, to have and to hold the name, status, style, title, honour and dignity of Earl of Devon aforesaid, with all and singular the preeminences, honours and other things aforesaid the said Edward and his heirs male for ever to him and his heirs aforesaid of the small customs of our Port of London by the hand of the collectors for the time being in equal portions, so that express mention, etc. These being witnesses, etc. (Peerage Law of England, p. 285)

The full list of the king or queen’s titles and salutation to the powerful of his or her kingdom had become so well understood that a full recitation is no longer necessary and a brief phrase in Latin would suffice. This form began in the reign of Henry I (1100-1135). It took about 300 years to evolve until the legal forms became so ingrained that a few simple catch phrases and/or abbreviations could capture the meaning and import for legal purposes. Also, the reasons cited had more to do with the favor of the monarch rather than an exchange of lands and rights for service.

As well as ensuring the salutation was consistent with standard practices, care was taken in finishing. The final wording had to ensure that nothing could be added afterward. In earlier documents, the addition of an “AMEN” or its abbreviation “A”, was often used for documents associated with religious houses. It was also common to sign off with “VALETE” or its abbreviation “VAL” – the word meaning “farewell to you”. In later documents, the end was often signaled by calling on the witnesses.

In addition, numbering was done almost exclusively using Roman numerals. While Roman numerals were sometimes cumbersome, Arabic numerals were almost unknown and did not have the weight of tradition to give them authority.

Certain conventions were used to prevent tampering. First, numbers were written with a period before and after. Second, the final (or only) i in a Roman number would be written j. For example, a clerk would write .j. for 1, or .viij. for 8. The v for 5, x for 10, l for 50, c for 100, d for 500 or m for 1000, had no altered form, but relied on the dot mark to define the number’s start and end. For example, the number 4 would be written .jv. (or .iiij. as a variant). So, if the date of a document was May 1, 1542, the date would probably read mai .j., .m.d.x.l.ij. Note the Roman numerals were usually written in lower case, although the capitalized version does occur.

Text Position

The text largely fills the page of legal documents in a solid block and usually without breaks for modern reading conveniences like paragraphs. Part of this was to avoid wasting valuable vellum, but it also helped prevent tampering with the contents of the document. The block shape of the text meant that adding a word or two was much more obvious and might be questioned. Margins are minimal on the sides, although there is space at the top and bottom that is potentially unprotected (more in Writing, Flourishes, and Decoration).

If the line of text did not stretch to the margin, it was common to add in a dot or tilde shape to cover the blank space (yet more on this under Flourishes and Decoration).

Writing, Flourishes, and Decoration

The handwriting itself was a security device. Certain styles of handwriting were normally used by clerks in creating legal documents, again reflecting the common base of understanding within the legal community. There is no one form of handwriting for legal documents; fashions in writing changed over the centuries and regional variations were common. However, what we call “chancery,” “cursive,” or “court” hands dominated in the production of most legal documents. Except where an unusual presentation or commemorative piece was given out, the “book” hands were rarely used. This is not to say that the writing on legal documents was sloppy. Readability was vital.

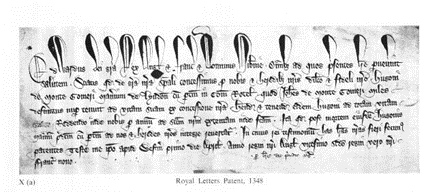

Figure 7 Simple cadel and extended uprights

The top margin of the legal documents usually had some blank space that allowed the uprights of letters to be extended and exaggerated, thus preventing any tampering in the first line of text. In addition, and perhaps in conjunction with these extended uprights, the initial word or two – normally the ruler’s name – could be written larger to emphasize both their importance and to keep anyone from altering the text. At times a clerk might add some drawings above the first line of text to decorate the document as well as protect the contents. The use of a cadel – a capital letter built of interlaced pen strokes – to begin the text is frequent in later documents.

The bottom margin was more vulnerable because a fair amount of blank space was needed in order to provide a place to attach the seals. As noted above, conventions in language helped ensure that nothing could be amended to the bottom of the text.

Indenture

While the above techniques were good for a single document, on occasion multiple copies of a contract were needed. How then to ensure that the copies were legitimate counterparts?

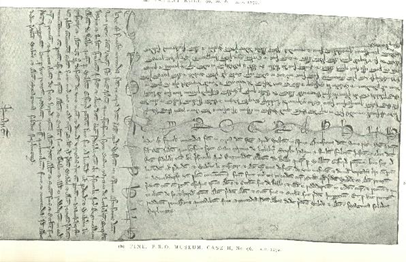

Figure 8 Rare complete 3-part indenture

The answer was the use of indentures. An indenture is simply a document with the same text written multiple times (normally two or three) on a single vellum sheet that was then cut into separate pieces. When necessary the cuts could be matched up to verify that the contract was the same for all parties. The term indenture comes from dens, the Latin word for tooth, reflecting the usual sawtooth or wavy pattern of the cut.

To further ensure the validity of the indenture, the word CYROGRAPHAM or one of its variants was written at the top of the document. It comes from Latin and roughly means “personal writing”. On occasion, the word INDENTURA was used. Both signified the clerk created a unique multi-part document. If the parts of the contract were joined, not only would the cuts have to match, but the handwriting as well.

Conclusion

The beauties of period legal documents may be more subtle than those of ornate illuminated books, but they have charms of their own. The same basic materials and skills are used to prepare legal documents. The examples given above are representative of the documents produced by the royal chanceries and monastic administrations, and I believe are a better model for SCA scrolls. Legal documents are a writ from the Crown, not a leaf from a book. Their purpose and function are more in keeping with the various creation documents that come with our award structure, at least at the peerage level. But for those who like a more ornamental document, there are choices there as well.

Figure 9 Document of Elizabeth I creating Cecil Baron Burley

References

Dixon, A. (2002). Women who Ruled: Queens, Goddesses, Amazons in Renaissance and Baroque Art. Merrell Publisher Ltd., London

Hall, H., ed. (1969). A Formula Book of English Official Historical Documents Parts I and II. Burt Franklin.

Hallam, E., & Prescott, A. (1999). The British Inheritance: A Treasury of Historic Documents. University of California Press.

Harvey, P., & McGuinness, A. (1996). A Guide to British Medieval Seals. University of Toronto Press.

Hector, L. C. (1958). The Handwriting of English Documents. Edward Arnold.

Johnson, C., & Jenkinson, H. (1967). English Court Hand: A.D. 1066 to 1500, Parts I and II. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. (Original work published 1915) Part I texts, Part II plates

Palmer, F. B. (2012). Peerage Law in England: Practical Treatise Lawyers (reprint). Forgotten Books.

Preston, J. F., & Yeandle, L. (1992). English Handwriting 1400-1650. Medieval & Renaissance Text and Studies.

Tannenbaum, S. A, (1967). The Handwriting of the Renaissance. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co.

Warner, George F. and Henry J. Ellis, eds. (1903). Facsimiles of Royal and Other Charters in the British Museum. Vol. 1, William I to Richard I. British Museum.