By Elizabeta Ferrofredo di Bari

In the 16th century, the Catholic church began certifying and shipping the relics of saints and martyrs across western Europe to restore vandalized churches and reinvigorate the Catholic faithful. Many of these relics were highly decorated and displayed to the people in churches and in processions. This project is a modern materials assemblage for camp decor, modeled on the relics stored in portable reliquaries for display and processing with the saint’s remains for veneration.

Catacombs fuels the Counter Reformation

The Roman Catacombs were rediscovered in 1578 – 150km of tunnels, over 40 chambers and perhaps half a million bodies of early Christians buried before the 5th century. Early visits by church leaders identified fairly few identifiable saints and martyrs; however, as their popularity increased, their careful examination became much more lax – common features of burials in inscriptions, art, or grave goods were quickly seen as denoting holy remains.

In the first survey of the Catacombs, Roma Sotteranea, priest Giovanni Severani described the remains as “weapons to fight against the heretics.” (Koudounaris) Pope Sixtus V established the office of the Sacred Congregation of Rites and Ceremonies in 1588 and the Custodian of the Catacombs to oversee the flood of interest that was starting. (Vatican) This office began identifying and sending out holy relics to churches throughout Europe starting almost immediately, and reaching enormous levels over the next 50 years – repopulating the furnishing of churches devastated by religious and civil conflict.

This happened along with the Counter-Reformation, a Catholic resurgence in response to the Protestant Reformation; it is generally dated as starting with the Council of Trent in 1545 – a religious strategy meeting that lasted 28 years. The Counter-Reformation inspired writings, religious movements, the founding of religious organizations and new religious works of art and music that culminated in the Baroque movement. The Baroque aesthetic in western Europe persisted until the 18th century. This artistic style was particularly popular in southern Germany and central Europe.

Roman Catacombs chamber, anonymous photo

Brief history of relics

Veneration of the bodies and body parts of Christian saints and martyrs was noted in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. It was criticized at the time by both early church leaders like St Augustine and pagans like the Greek philosophers Celsus and Vigilantius. (Oneonta) Augustine changed his view of this practice over his life and it became a common feature of Christian practice. Defense and criticisms of saint veneration and relics are argued in Thomas Aquinas’s work Summa Theologica. (Part III Q 25). Throughout the Catholic church from the 9th century on, church buildings included a saint’s relic to sanctify their altars. Early relics were generally small body parts kept out of view in enclosed coffers, sometimes sculpted to depict the interior body part.

12th c example of enclosed reliquary, Limoges, France held by the British Museum © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons and Example of a body part reliquary, Arm of St Valentine, Basel Switzerland, 14th C. Held and photo by the Metropolitan Museum of Art

During the Protestant Reformation, veneration of relics and the propagation of pilgrimage were seen as fraudulent and exploitative, and were a common target for critics of church practices. During the Reformation many relics were destroyed, hidden, or removed and sold, emptying churches in many regions. These events were sometimes called iconoclasm or beeldenstorm. What had been a traditional trade in relics (or outright theft – see St Martin by Tours, St Nicholas by Bari) among the faithful for centuries became an avalanche of religious fervor during the Counter-Reformation.

New Holy Bones For the People

As Rome began sending holy relics to repopulate these farflung parishes, guilds, and even private chapels of wealthy Catholic families (a process called “translation”) new artistic display aesthetics were happening, incorporating open display of the actual remains – perhaps a “transparent” response to Protestant criticism. This is an evolution of the memento mori (remember me) depictions of death and mortality in Western art – and perhaps also influenced by explicitly graphic corpse depictions of the transi tombs popular from the 14th century – 16th century.

Example of a transi tomb Jacques du Broeucq’s 16th-century “l’homme à moutons” (“man eaten by worms”) in Boussou, Belgium. Jean-Paul Grandmont/Wikimedia Commons

Example of skull relic in portable container. Saint Ivo of Kermartin, Tréguier, Brittany, France, Derepus/Wikimedia Commons

Modern example of reliquary procession, St Thomas Aquinas, Pravero, Italy 2024 Daniel Ibanez/Catholic New Agency

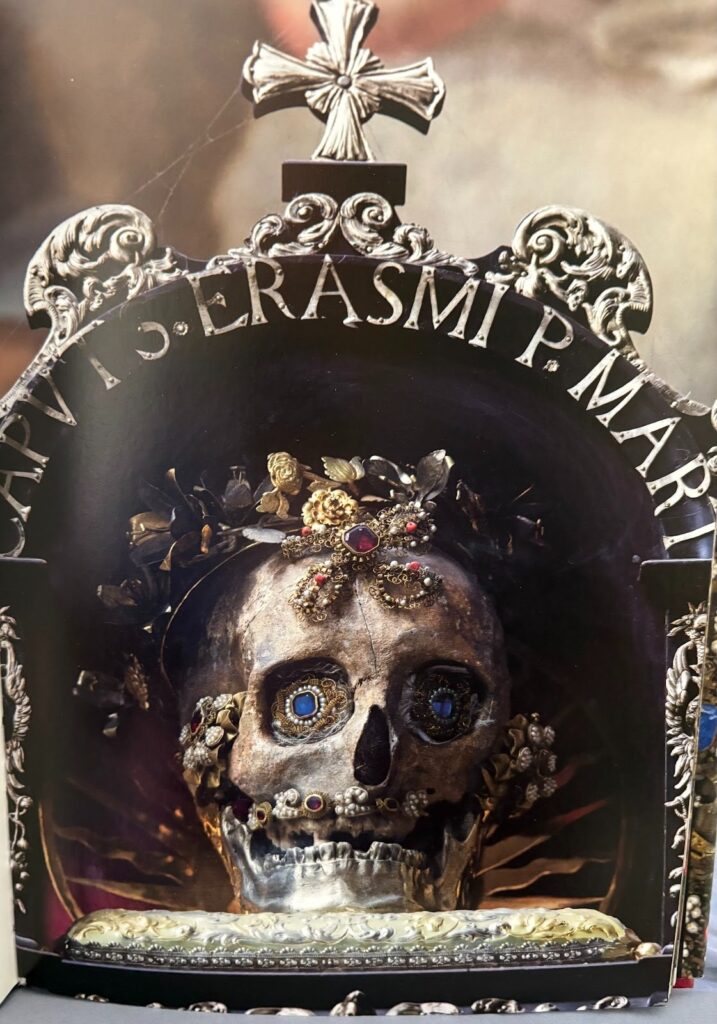

When remains arrived at their new homes, local people in holy orders, usually nuns, took charge of their decoration. Here, local preferences were apparent. Germany, Switzerland, and central Europe heavily jeweled the remains, sometimes with ornate clothing and objects associated with the saint. Sometimes a transparent silk veil was used to give a soft filter and prevent dust accumulation.(Koudounaris) The remains were adorned with commissioned works as well as jewelry donated by the local faithful, ranging from highly rare and valuable to the more accessible semiprecious and paste faux jewels and baser metals popular at the time.

In later centuries these artistic choices were seen as macabre and the remains were quietly stored away or redecorated with more camouflaging fabric coverings and masks. Often the originals survive only in more obscure churches, in storage, or memory.

St Erasmus, Munich, Koudounaris

This project:

This faux relic camp decor project echoes the coffered shape and portability of historic reliquaries, ready for use in processions. In honor of St Barbara, patron of armorers, this faux skull is decorated with distressed gold leaf and adorned with glass and semiprecious jewelry with a number of recycled materials in the style of the early Baroque period. The second, in honor of St Mercurius, “wielder of two swords” contains a replica of Greek-style funerary crowns found in several extant burials, is coated in the yellow clay typical of the Mediterranean and contains faux jewel decoration and reproduction coins. His warrior’s skull is open to contain the offerings from pilgrims and rests on a fur cushion accompanied with animal bone and human hair.

Extant example of funerary crown, Lato, Greece, 1st century held and photo by Agios Nikolaos Archeological Museum

Child with wreath of fruits and flowers, 3-4th century bce Patras, Greece. Gilt and clay. Held and photograph by Archaeological Museum of Patra

Roman funerary wreath – 1-2 century ce – during the Catacombs era. Held and photo by the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Process

Painted metal box, used sprayed glue and imitation gold leaf to make a distressed, gilded skull. Adorned with recycled jewels, fabric, artificial flowers. Eye gems are intaglio carved stones, a Roman style recycled in later period jewelry. Funerary wreath skull was distressed with a paste of yellow ochre clay, a gilded wreath with faux pearls, fabric, and reproduction coins added, along with donations of human hair and animal bones. Third skull gifted to Caitilin Inghean Ui Ruaidhri was distressed with hardwood charcoal dust and decorated with paper flowers, fabric, faux pearls, glass, and semiprecious stones.

Charcoal Distressed:

Before:

Distressed with yellow ochre:

Are the jewels real?

Jewelry including faux materials – glass, semiprecious stones, pastes, and enamel used to imitate more rare and valuable jewels – and using baser metals instead of valuable ones, sometimes with a coating or treatment, existed from ancient Greece (or earlier) through the modern era. Clay and gilt rather than solid gold form children’s funeral crown pictured, Roman recipes survive for faux pearls, and imitation jewels are seen in the Elizabethan and Jacobean jewels from the Cheapside Hoard, a jeweler’s hoard rediscovered in London in 1912

In Closing:

This was inspired by the Heavenly Bodies display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018, the personal desire for 16th century examples of heads on stakes, and the theme of the event Festival of Bones. My camp appreciates I stopped with skulls.

Works Cited:

Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica. 1274. Logic Museum, https://www.logicmuseum.com/wiki/Authors/Thomas_Aquinas/Summa_Theologiae/Part_III/Q25.

Boehm, Barbara Drake. “Relics and Reliquaries in Medieval Christianity.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 April 2011, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/relc/hd_relc.htm. Accessed 4 November 2025.

Bolton, Andrew. Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018.

Cleveland Museum of Art, and British Museum. Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe. Edited by Martina Bagnoli, et al., British Museum Press, 2010.

“Counter-Reformation | Definition, Summary, Outcomes, Jesuits, Facts, & Significance.” Britannica, 24 October 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/Counter-Reformation. Accessed 30 October 2025.

Koudounaris, Paul. Heavenly Bodies: Cult Treasures And Spectacular Saints From The Catacombs. WW Norton, 2013.

McLaughlin, Meredith. “Arm Reliquary: Journey from Divine to Fine Art.” Medieval Art and the American Public: A Digital Narrative, Fordham University, https://medievalartus.ace.fordham.edu/exhibits/show/arm-reliquary/arm-reliquary-essay.

Nuwer, Rachel. “Meet the Fantastically Bejeweled Skeletons of Catholicism’s Forgotten Martyrs.” Smithsonian Magazine, 1 October 2013, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/meet-the-fantastically-bejeweled-skeletons-of-catholicisms-forgotten-martyrs-284882/. Accessed 30 October 2025.

“Reliquary Arm of St. Valentine – Swiss.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/464332. Accessed 4 November 2025.

“The Sacred Congregation of Rites.” Dicastery for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments,, Vatican, 2024, https://www.cultodivino.va/en/chi-siamo/storia/la-sacra-congregazione-dei-riti.html. Accessed 28 October 2025.

SUNY Oneonta. “Cult of the Relics.” Art History 212 http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth212/relics.html

Costs – I like to keep an estimated record of project costs.

Box 10$ each

Skulls 15$ each

Gold paint 8$

Gold leaf 6$

Glue 8$

Jewels and coins 15$

Wreath 10$

Ochre 8$

Book 20$

Rabbit holes – topics I encountered during the project I didn’t pursue. Yet.

Ossuary and bone art

Guilds and their patron saints

fancier relic boxes with carved and turned wood

Beheaded saints

Appearance of early modern displayed heads post execution

Relic and mourning jewelry

Funeral meals

Hussite wars

About me: I’m a rapier and cut and thrust fencer from northern Atlantia. My first A&S project was Viking blood bread in Sept 2024, and I’ve also done projects on parasite remedies and their recipes, Chinese poet Li Qingzhao, and on zibellini. In my project queue is a batch of garum, a willow branch fish trap, and lot of of gelatin.