By Lord Alexander of Ayr

Description:

The scabbard serves to store and carry a sword when not in use. It further serves to protect the blade from water and other oxidizers, as well as protect random objects from coming into contact with the sword’s edge. The leather extension on the handle that covers the opening of the scabbard provides additional protection from the elements.

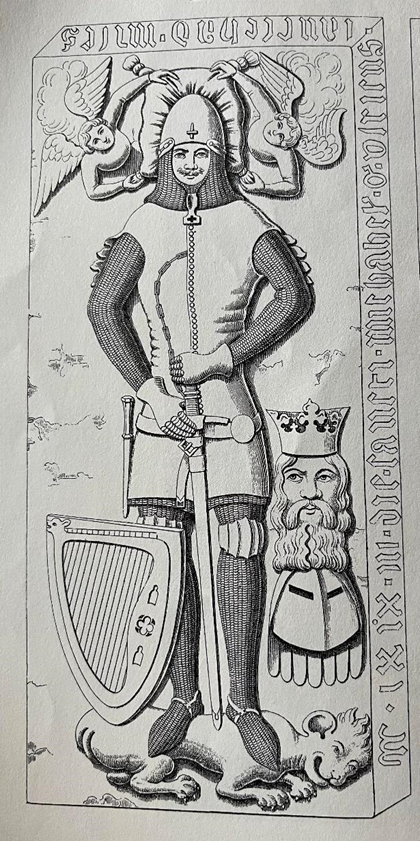

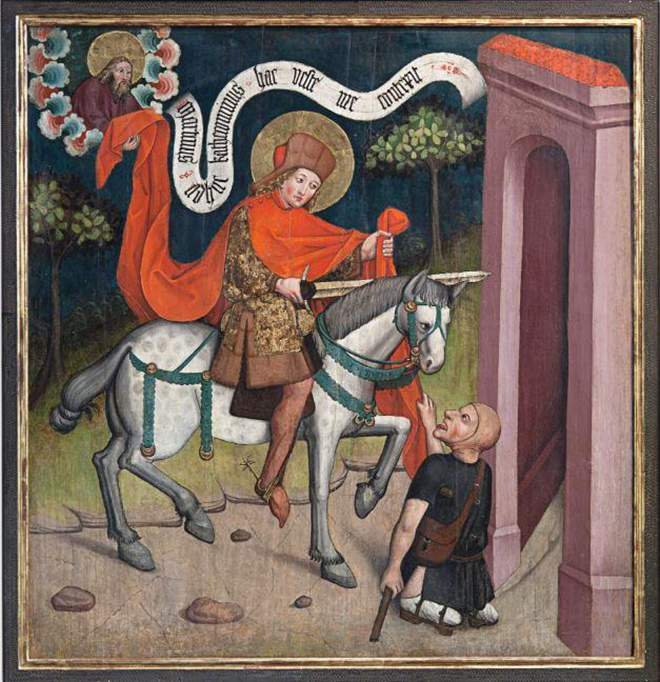

This scabbard is based on artistic depictions from 14th-15th century in western and central Europe, as well as modern reproductions which I found quite motivating. Examples of scabbards from this time period include the depiction on Ulrich Landschaden’s funerary monument (1369), Peter of Stettenberg’s funerary monument (1441), and a painted panel of Saint Martin parting his cloak (around 1460-70) in the Rottenburg Diocesan Museum. For reference photos, please see the attached documents.

Supplies:

- Four pieces of wood or plywood (between 1/4 and 3/8 of an inch think)

- 2 pieces – longer than the blade of the sword, and a bit broader (preferably by at least 1/2 inch or so in both dimensions)

- 1 Base board

- 1 Top board

- 2 pieces -at least 1 inch wide, and long enough to run most of, if not the entire, length of the edge of the sword’s blade (if they are short by an inch or so, that’s fine).

- 2 Side boards

- 2 pieces – longer than the blade of the sword, and a bit broader (preferably by at least 1/2 inch or so in both dimensions)

- Leather

- 4 mm

- .8 mm

- Artificial sinew

- Wood glue

- Preferred dye or paint

- Acrylic seal

- Brass sheet (18 gauge -20 gauge is probably best)

- Two-part epoxy

Tools:

- Saw (hand saw and/or jig saw)

- Dremel tool (with bits to cut metal and sand wood)

- Sandpaper

- 250 grit, 800 grit, 2,000 grit, 5,000 grit, 7,000 grit, and 10,000 grit

- Leather punch (leather punch stamp)

- Leather sewing needle

- Permanent marker

- Clamps

- Paint brushes

- Ballpein hammer

- Dishing form

- Stout Scissors

- X-acto knife or a very sharp knife

- Plyers

- Tin-snips or equivalent

- Safety goggles

- Leather gloves

- Power drill

Part 1: Woodwork

Begin by placing the intended sword to be sheathed on the base board. Take the permanent marker and trace the blade of the sword on the base board. The sword should then be removed and placed somewhere safe but close at hand. Make sure that there is at least ¼ to ½ an inch extra wood on each side of the tracing on the baseboard, and an extra 1 inch of wood past the point.

Take the two side boards and line them up with the tracing of the sword’s blade. If they are the appropriate length (roughly the length of the blade edge), apply glue to one side of each of the two side boards. Then press the glued side against the base board along the outside of the traced line. Apply clamps to hold the side boards to the base board. If the clamps are not long enough, apply weight on top of the side boards pressing onto the baseboard. I recommend free weights or particularly academic books. Leave in place for 24 hours or however long the glue’s instructions indicate is necessary to fully cure.

Once the glue has cured, pass the sword into the opening that will be the resting place of the blade in the scabbard. Any irregularities that prevent the sword from moving cleanly through the channel (slinters, glue bulges, etc.) should be removed at this time. Once this is done, mark at least ¼ of an inch out from the interior channel on the two side boards. Make a line at this distance that runs the length of the two side boards. These will be your cut lines.

Carefully cut away the extra wood along the lines you marked. Then take the top board and place it on top of the wooden channel you made. Hold the top board against the wooden channel and then slide the sword into the opening. If it seems to pass in and out unobstructed, then it is ready for gluing.

Apply glue to the top of the side boards and spread it evenly (removing the excess) with a paintbrush. Then place the top board on the glued sideboards. Clamp the boards and wait for the glue to harden. Again, if the clamps won’t work for some reason, seek out those other heavy objects to pile on top of your project.

Once the glue is dry, cut away the excess of the top board that hangs over the rest of the scabbard. Once you finish those cuts, you have a scabbard! A blocky and bare scabbard, but a scabbard none the less.

Prepare for sanding! For the sake of sanity, I recommend using a belt sander to round off the sides of your scabbard. However, a Dremel tool and 250 grit sandpaper will also work (albeit, it will take a lot more time, but we all make do with what we have). It is theoretically possible to use only sandpaper or a file to round off the scabbard. For the sake of time, I would not recommend it. When you are done, the scabbard should have a reasonably uniform and oval profile, allowing you to comfortably hold it in your hand.

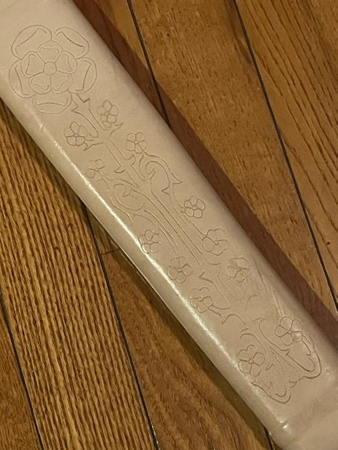

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Part II: Leatherwork

Determine where your suspension belts will go on your scabbard. To an extent, this is a matter of preference for how you want the sword to hang at your side. For this piece, the suspension belts are about ½ wide, so the combined space the belts will cover will be 1 ½ inches each. Further, one will need to be near the top, the other closer to the middle. Glue thin strips of leather (about ¼ inch wide) 1 ½ inch apart. Let them dry completely. These will form rises under the cover leather to keep the suspension belts in place.

Trace the top of the scabbard opening onto the 4mm leather with your marker. Cut out this shape. You should have a leather disk the size of the scabbard opening. Glue this disk over the scabbard opening and let it set. Once the glue is dry, cut a slit into the disk to slide the blade into the new opening. Carve away at this slit until the blade can pass completely through the opening. The opening should be tight enough to keep the sword from accidently falling out, but loose enough to allow the sword to be drawn with minimal effort.

Take your 0.8 mm leather and lay it out. Place your scabbard on the leather and position it in such a way to ensure the leather will run the full length of the scabbard and completely envelope it. Carefully mark how much leather will be used to completely and tightly wrap the scabbard, then cut it out. If it is slightly too small, don’t worry about it. Along the edges where you will sew the leather around the scabbard, punch a series of holes to enable stitching. After this, completely soak your leather. I used a sink, but your living companions might object to this. In which case, a bathtub or a bucket will also work. Wipe away the excess water from the leather before wrapping the scabbard.

Now the sewing begins. Take your artificial sinew and your needle and begin sewing your leather over the wooden core. Try to move quickly, as the leather will grow taught and stiff as it dries. You can take a wet cloth and re-wet the leather as you go if you need more time. For aesthetics you may wish to keep the knots of your stitchwork on the inside of the leather. Once done, tie strings around the edges of your risers to assist the leather in forming tightly around them.

A similar process was followed for the handle. First, I stripped off the existing leather from the handle. However, before replacing the leather, I measured and cut out a rainguard.

The rainguard was done by trial and error, but I eventually settled on two pieces on 0.8 mm leather, in oval disks, about 3.5 inches by 5.5 inches (if you have 2mm leather, I recommend this). If your sword’s pommel detaches from the handle, cut an opening just large enough to slide the rainguard up the handle when the leather disks are wet. If the pommel doesn’t detach (like this sword), cut the opening just large enough to slide the rainguard over the pommel and up the handle to the crossguard. You can then stitch the opening on the rainguard closed as the leather dries for a tighter fit. While the rainguard is still wet, slide the sword into the scabbard, and mold the damp rainguard around the opening. You can hold it in place with clamps, but maybe put some foam between the clams and the leather to prevent an unwanted indentation. I found that sewing does most of the work. You can stitch the rainguard over the crossguard to help hold it in place while the leather is still wet. Once dry, apply some glue between the 0.8 mm pieces of leather to hold them together.

For this handle, once the leather was off, I glued a thin leather strip on the middle (about ½ an inch wide) to form a riser. Then I measured how much 0.8 mm leather was needed for the handle, cut it out, punched holes, wet it, and sewed it on.

Fig 3.

Fig 4.

Part III: Decoration

If you were looking to tool the leather, it is probably too late. However, minor tooling, dying and painting are still an option. I drew my patterns onto sticky notes or printed them out and affixed them to the moist leather. Using a sharp pencil, I traced over the patterns onto the leather. This leaves an impression in the leather that lasts even after it dries.

Fig. 5

Apply your dye to the scabbard in thin, even coats. Try not to stop mid application to avoid color inconsistencies. Also, be sure to test your dye on a scrap piece of leather first to make sure the leather you are using will absorb your dye. Apply a layer of acrylic finish to keep the dye from bleeding through. You may need more than one coat of finish. Once the base color is done, you can apply the details. I used red for the base color of this scabbard. For details I used white, black, and gold. For paint, I used a paintbrush for miniatures. For very fine lines and details, I used a toothpick. Apply finish again over the paint for protection.

The person this scabbard is for, Master Morian MacBain, wanted Maltese crosses (which are part of his heraldry), thorns, roses and Tudor style roses. Based on these guidelines, I made the designs, traced them onto the leather, and painted them in. The scabbard’s colors consist of red, black, and white (Morian’s heraldic colors), as well as gold to help tie together the brass pieces in the work. There are three Maltese crosses on the scabbard, reflecting Morian’s heraldry, as well as 14 roses including one large black and gold Tudor style rose.

Fig. 6

(The motto is in Latin, and reads “Viam Inveniam Aut Faciam.”

This translates to mean “I find a way or make one”).

Step IV: Metalwork

The chape is a small piece of metal that cups the bottom of the scabbard. I began by measuring the scabbard’s bottom to ensure it would roughly be the right fit. I then measured and used the Dremel tool to cut a general shape out of a piece of sheet brass. Using the Dremel tool and some metal cutters, I then ground and cut the piece further until it was a flattened shape of what I wanted. For much of this process, I held the brass with pliers as the metal became exceptionally hot. Brass dust and shards were a common occurrence (wear eye protection). Using a set of robust pliers, with the mouths wrapped in leather, I bent the chape into shape. I believe I used 16 gauge, but I would probably recommend 18 or 20, as it is easier to shape and the additional strength is not needed.

I applied a two-part epoxy to the inside of the chape and secured it to the end of the scabbard. It did not stay in place easily, so I had to tape it while it dried. After it is secure, use increasingly higher grit sandpaper to polish the chape to remove any imperfections.

Finally, there are the suspension belts. They are made from strips of between 2 and 4 mm leather. 2 mm is probably all you need for a sword of this weight. Dye the belts your preferred color and then seal. The buckles were made by Raymond’s Quiet Press. Using more sheet brass, measure out 2-3 1.5 by 0.5 inch rectangles (depending on your suspension system). Drill an elongated hole in the middle of the rectangles, bend the rectangles in half with the hole in the middle (hamburger style), and pass the buckle through the rectangle with the tongue of the buckle coming out through the hole. Now pass these pieces over the ends of your suspension belts. Clamp the brass pieces in place, drill a hole in the brass rectangle and through to the other side. Finally, rivet it all together. Tie your suspension belts around your scabbard and to your sword belt. Adjust your set-up until it feels right.

Step 5: Conclusion

At the end of this process, you should have a scabbard roughly like the one I made. Thank you for your time and consideration.

Fig. 7

Thanks:

To Master Morien MacBain, for inspiring me and for your unending support.

To Master Otto Boese of House Sable Maul – your class on scabbard making six years ago motivated me to give this a shot (though it was a long time coming, and I confess I probably misremembered half of what you taught).

Peter of Stettenberg monument (1441)

Ulrich Landschaden monument (1369)

Saint Martin parts his cloak

Painted panel around 1460-70,

Rottenburg Diocesan Museum

Mantelteilung des heiligen Martin, Meister des Riedener Altars, Schwaben (Ulm?), um 1460/70, Inv. Nr. 2.1

https://dioezesanmuseum-rottenburg.de/en/diocesan-museum/collection

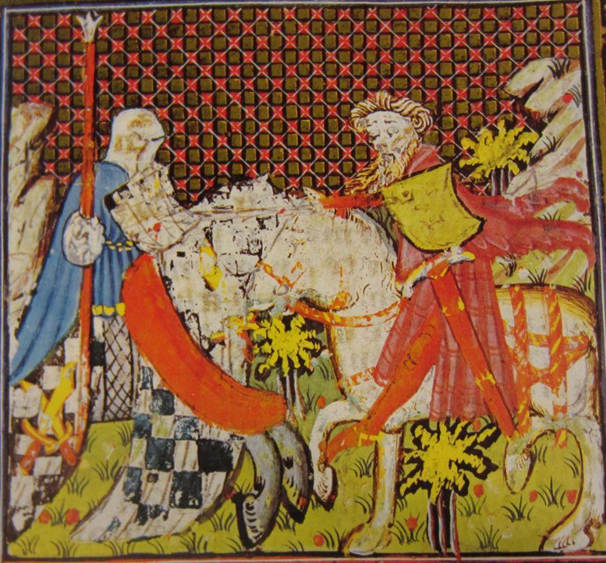

Saint Peter and Maria

1375-1385

Cologne, Germany

https://effigiesandbrasses.com/1813/5128

A.

B.

ONB Cod. 2537 Roman de Tristan

National Library of Austria

1410-1420

French