by Doña Mariana Ruiz de Medina

The below paper was written for Cultura Atlantia at the Coronation of Afshin and Yasmine. If you have any questions on my work, please feel free to check out my website at www.marianaruizdemedina.com.

Trade Route to Table: The Origin of Cooking Spices

Objective

For previous projects, I have developed several spice blends based on the recipes in Ruperto de Nola’s Libro de guisados, manjares, y potajes. There are a total of 12 different spices mentioned in those blends, the vast majority of which are not cultivated in Spain, where my persona is from. I had never before considered where each of these spices originated and how they might arrive in my persona’s kitchen and wanted to take the opportunity to better grasp some of the globalization of her time.

Context

My persona focuses on the mid-15th century in Spain, specifically near Valladolid in northern Spain. This was the seat of the Spanish monarchy at the time, which would be a driving force of commerce through the area. She is middle class and the daughter of a landholder. This would afford her some of the finer things in life, particularly where food was concerned.

The recipes themselves come from a 16th century cookbook. However, while the earliest known version of this cookbook is 1520, scholars largely believe it is not the first ever edition, simply the first we know of. More of my research on the cookbook itself is available here.

The Recipes

Spices for Common Sauce

Original text:

Three parts cinnamon, two parts cloves, one part ginger, one part pepper and a little dry coriander, well-ground, and a little saffron if you wish; let everything be well-ground and sifted.

Ingredients:

- 12 grams ground cinnamon

- 8 grams ground cloves

- 4 grams ground coriander

- 2 grams ground ginger

- 2 grams ground pepper

- 3 medium pinches of saffron

- This is not a precise measurement because the quantity added was too small for my scale to measure. I added saffron until a faint hint of vanilla could be smelled. Because saffron is so fat soluble, it shows up more potently in food than it does in this blend.

Potential additions of mace and nutmeg to this recipe come from both the Libre del Coch and the Libro de Cozina. I added 1 gram of each so as not to overwhelm the main mixture but to still be able to smell and taste them.

Spices for Peacock Sauce

Original text:

Four ounces of cinnamon, one ounce of cloves, one ounce of ginger, enough saffron to color the sauce well, let it be well-ground and sifted; some add grains of paradise.

Ingredients:

- 16 grams cinnamon

- 4 grams ground cloves

- 4 grams ground ginger

- 2 grams grains of paradise, hand-ground

- 2 generous pinches of saffron

- As with above, I added saffron until I could lightly smell it.

The translator of my Nola text indicates in footnotes that earlier versions of the text specific ½ oz of saffron and ¼ oz grains of paradise. Later in the text there is a more detailed recipe for Peacock Sauce that I have not attempted yet, but makes use of this spice blend with almonds, liver, vinegar soaked bread, and egg yolks. This formula is fairly standard for sauces in this book, but diverges in that it uses uncooked egg yolks instead of hard boiled egg yolks like others.

Duke’s Powder

Original text:

Half an ounce of cinnamon, one eighth of cloves, and for the lords cast in nothing but cinnamon, and a pound of sugar; if you wish to make it sharp in flavor and [good] for afflictions of the stomach, cast in a little ginger.

And the weights of the spices in the apothecary shops are in this manner: one pound is twelve ounces, one ounce, eight drachms; one drachm, three scruples; another way that you can more clearly understand this: a drachm weighs three dineros, a scruple is the weight of one dinero, and a scruple is twenty grains of wheat.

Ingredients:

- 170 grams sugar

- 56 grams ginger

- 28 grams cinnamon

- 28 grams long pepper

- 28 grams grains of paradise

- 28 grams nutmeg

- 2 grams galingale

- Cardamom, see note below

- Cloves, see note below

The additional spices come from the Libre de Sent Sovi and Libre del Coch. While the original Nola recipe is a very versatile spice blend, incorporating the other spices mentioned in these other books brings much more depth of flavor.

Note: My variation on the powder includes 2 pods of cardamom for every 15 grams of spice blend and 1 gram of cloves for every 15 grams spice blend. The original recipe itself is particularly interesting for its peripheral discussion of weights and measurements.

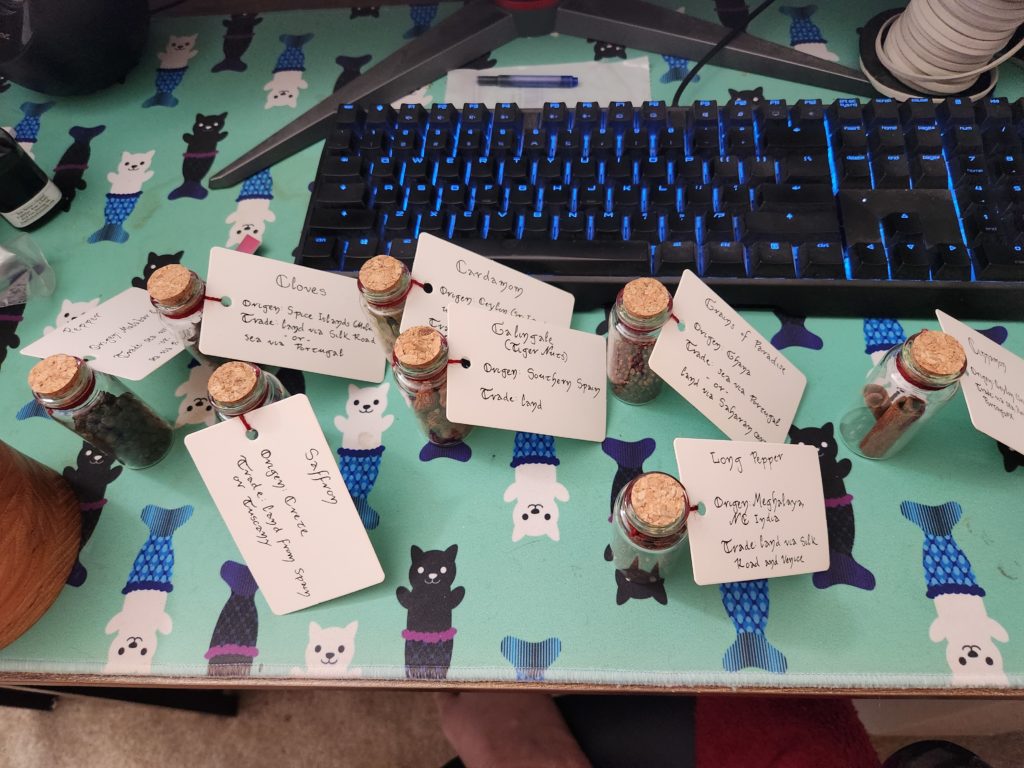

The Spices

The 12 spices explored for this project are: cinnamon, cloves, coriander, ginger, cardamom, grains of paradise, galingale, saffron, long pepper, pepper, nutmeg and mace, and sugar. As a category, spices in period were much more than the culinary focus we have today. Many of these would have a role in medicine, religious observance, cosmetics, and perfumery as well. Spice trade was a major driving force in European colonialism at the time and an extraordinary amount of spices were used in cooking at the time. While some of this can be attributed to conspicuous consumption, the genuine enjoyment the European palette had for spice should not be understated.

Cinnamon

Cinnamon has a slightly contentious origin story. One variation, called “true cinnamon,” is endemic to modern day Sri Lanka, called Ceylon during my persona’s period. Arab invaders reached Ceylon in the 10th century and controlled the area well into the 15th. In the 16th century, after Vasco de Gama’s voyages, Portuguese trade routes took over the area followed by the Dutch in the 17th century who established cinnamon plantations. The other primary commercial version of cinnamon, Cassia cinnamon, comes from China. Ceylon cinnamon is regarded as the more pure and valuable of the two, due to its cleaner flavor and lower levels of coumarin (a potentially poisonous compound found in both versions). Ceylon cinnamon would have made its way to Spain via sea routes with the Arabs and Portuguese whereas Cassia cinnamon would have made its way overland on the Silk Road. Cinnamon was one of the four major commercial spice crops at the time and was among the most valuable.

Cloves

Cloves originate in the Molucca Islands, or Spice Islands, in the Indonesian archipelago. Its path of trade first existed between the various islands, where it was traded for critical foodstuffs, then into mainland China in 200 BCE, overland to Venice and Constantinople. Cloves are featured in Arthurian Grail legend as well as 14th century English guild regulations. This spice was of particular economic importance in Venice, prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in the Spice Islands in 1514. Part of the myrtle family, cloves themselves have been used as local anesthetics in dentistry as well as to freshen breath and other medicinal uses due to a compound called eugenol. Both Ayurvedic medicine and Greco-Roman naturalists like Pliny encourage the use of cloves during feasting, for gut ailments, and fragrance. Cloves would most likely have reached my persona’s table via Portugal during her lifetime, but would be well known via Italy beforehand.

Coriander

Unlike most of the other spices on this list, coriander originates as part of the carrot family from Anatolia. Used for both its seeds and leaves, early mentions of the plant date back to 2500-1500 BCE in Egypt for medicinal uses, as well as Akkadian recipes from Mesopotamia. Coriander was traded out from the Middle East into China, where the main word for coriander has Farsi roots. All major Greco-Roman food treatises and natural histories included this spice, and that it was relatively easy to grow throughout the empire. Like many things, coriander grows well in Spain and would have been easily cultivated in my persona’s home garden.

Ginger

The ginger family includes some of the most economically important spices of this discussion, not just ginger, but also cardamom, turmeric, grains of paradise, and galangal. Ginger itself for the purposes of this discussion is the same rhizome (root) that we consume today, in many of the same forms: dried, powdered, and fresh. The first word for ginger comes from Sanskrit, and it has been cultivated in China for 5000 years- Confucius also mentions it in his medical notes. From mainland China, ginger made its way into Indonesia and India, where it encountered maritime traders from the Middle East. From there, ginger was brought to the Iberian Peninsula by the 6th century and is even mentioned by name in the Qur’an. By the mid-15th Century, ginger could still be coming via Moorish trade routes, but also potentially reach my persona via Portugal. Along with cinnamon, ginger is also one of the four most economically important spices of our period.

Cardamom

Cardamom can be a contentious flavor- in small amounts it has a piquant vanilla like note but too much and it easily tastes medicinal. Generally, sources agree that cardamom originates in India, but where precisely isn’t quite clear. Some say Ceylon, others say the Western Ghats in Southern India, and others say Kerala (a more specific part of the Ghats). Cardamom is mentioned in Ayurvedic medicinal texts dating to 1400-1600 BCE. The spread of cardamom throughout the world can interestingly be tracked through the words used for the spice. In areas where cardamom was brought via land (i.e. most of Europe), the root of the word is closer to the Greek and Indian words for it. In areas like the Middle East and Africa, the words more closely mirror the Arabic word for the spice, indicating its origin in Arabic seafaring trade via the Arabic Gulf and the port of Alexandria. Portugal as well included cardamom in their manifests over sea, and this or Mediterranean seafaring is the most likely source my persona would have had.

Grains of Paradise

Grains of paradise are also part of the ginger family, however their origins are in tropical West Africa. These small, piquant spice grains come from Ghana and are sometimes called malagueta pepper. They were first brought to Europe in the 13th century, likely via the Portuguese over sea or via the caravan trade routes through Saharan Africa. The height of their popularity was during the 14th and 15th centuries and either way, they generally entered continental Europe via Morocco and the Strait of Gibraltar into Spain.

Galingale

Nola’s works and the auxiliary works that informed my spice blends specifically use the word “galingale” in their recipes. The simple interpretation is that this refers to the ginger family member galangal. This spice is used for its root, much like ginger, and in Chinese the word for galangal even means “mild ginger.” There are multiple types of galangal: greater galangal is from the Indian subcontinent and lesser galangal originated in China. Generally the spice is used in its root form and would travel over land from China into Europe or via sea from India. The word galangal itself is the Arabic translation/transliteration of the Chinese word for the plant.

However, galingale can also be used to refer to small tuberous plants from the cyprus family, that we know today as tiger nuts. In Spanish, these tubers are called chufa and are hugely popular in Valencia, where they are thought to be the origin of modern day horchata. This was the spice I chose to use in my blends. Tiger nuts are grown in southern Spain along the coast and widely in Valencia. References are made to galingale being boiled in honey or sugar to soften them and make them sweeter. Their flavor is mild, fruity, and almondy.

Saffron

The third of the major economically important spices, saffron is still to this day one of the most expensive substances by weight on the planet. The tiny stamens that have to be harvested by hand from the bright purple crocus are pungent, aromatic, and have uses as medicine, dye, cosmetics, perfume, and more. Genetically, saffron crocuses come from Crete in the Bronze Age. Some of the first visual depictions of saffron are in frescoes preserved in a volcanic eruption in Minoa in 1600-1550 BCE. A Greek myth about a man named Crocus and his nonconsensual pursuit of a nymph are documented in the vernacular. Egyptians valued saffron for its many uses as well and Cleopatra is said to have bathed in it before meeting her lovers (however, this information should be considered biased as much of Cleopatra’s scholarship contains prejudices against her for wielding power as a woman in a patriarchal power structure). Saffron cultivation is possible throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East, however Tuscany was the major agricultural center for saffron for quite some time. Saffron for my persona would have likely been Italian in origin, if not domestically grown in Spain.

Long Pepper

For much of the Middle Ages, long pepper was by far the more popular type of pepper available to consumers in Europe. This compound pepper berry was shipped dried and then ground into powder. The word for pepper in India, pippali, is considered the etymological root of our modern word “pepper” instead of the Latin capsicum. Long pepper was particularly popular in warmed drinks like hippocras and was so valued that Domitian stock piled the spice to use as currency and Alaric the Visigoth demanded pepper as part of his ransom after sacking the city of Rome. The berry itself comes from Meghalaya in North Eastern India. Its production largely went overland due to its close proximity to China. Like many Indian spices, it has a role in Ayurvedic medicine. Most likely, long pepper would have reached Spain via Venice and the Silk Road trade into Italy.

Pepper

Black pepper overtook long pepper in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance in popularity. It grows on the Malabar Coast, and once the maritime trade routes back to Europe were more firmly established, black pepper became more economically viable than long pepper. That is not to say that black pepper was not available prior to this rise in popularity. Black pepper first reached Europe in the 4th century with Alexander the Great, has mentions in Han and Tang dynasty records, and is even present in Egyptian mummifications. Roman conquest brought the spice to Europe via Suez and the Arabian Gulf but it was the Portuguese that truly streamline pepper as being so economically important that both Vasco de Gama and Christopher Columbus set out to find it. Black pepper would have been common in Spain both through maritime trade on the Mediterranean sea and via Portugal during my persona’s lifetime.

Peppercorns harvested at different stages produce different results. Black pepper comes from almost fully ripened berries that have been fully dried. White pepper comes from fully ripe berries that have been skinned and then dried. The flavor is more mild because much like grapes, the skin contains all the anthocyanins and tannins. Green pepper is under ripe berries that have been brine preserved instead of dried. Pink pepper on the other hand comes from a different, but related, plant from South America.

Nutmeg and Mace

While nutmeg and mace come from the same plant, the spices themselves have interesting differences. Where nutmeg is the smoother, warmer flavor, mace is much more piquant and bright. Mace comes from the covering of the nutmeg, starts off a rich red color, and then gets fired. It can be used either in flake form or powdered. Hancock explains the route of the spice origins best as, “Sailors from India and Sri Lanka were traveling to and from Bali, Java, and Sumatra across the Bay of Bengal. Indonesian seafarers were conducting trade within the center of the vast archipelago itself. Indonesians reached out into Southeast Asia and China.” Both spices are first mentioned in India in 1500-1600 BCE for neurological ailments and then later cardiac ailments. The first mention in China of nutmeg occurs in the 3rd century, followed by Europe in the 5th or 6th century. Pliny may possibly make a reference to it, but it is unclear. The first definitive European reference is Byzantine. Arabic scholars dating back to the 10th century under the Abbasid caliphate have included both nutmeg and mace in medicinal textbooks, and it is very likely that this is the route by which both spices entered Spain. Galen’s humoral theory served to further popularize the spices in continental Europe.

Sugar

Last but certainly not least is something that we modernly do not consider a spice, but very much was at the time of my persona- sugar. For much of the history of continental Europe, and indeed for many of the less economically privileged, honey was the primary source of sweetener. Cane sugar is native to New Guinea and migrated into India via Indonesia and the Philippines. From there, Arab traders brought the cane to the Middle East and greatly expanded its cultivation. In the 10th century, under the Nasrid caliphate, sugar cane was brought to the Iberian peninsula, where it flourished in the southern regions and Valencia. Egyptian manufacturing allowed for the extraction and refining of sugar into more usable forms. However, sugar in my persona’s life would still have been very much a luxury. Honey would be more common in use, but for these spice blends, and much of Nola’s cookbook, sugar was used as a finishing touch.

Works Cited

Black Pepper. McCormick Science Institute, https://www.mccormickscienceinstitute.com/resources/culinary-spices/herbs-spices/black-pepper.

“Black Pepper.” Edited by Melissa Petruzzello, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/plant/black-pepper-plant.

“Cardamom.” Cardamom | Silk Routes, University of Iowa, https://iwp.uiowa.edu/silkroutes/cardamom.

“Cardamom.” Medicinal Spices Exhibit – UCLA Biomedical Library: History & Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles, 2002, https://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?displayID=3.

Chen, Angus. “Loathed by Farmers, Loved by Ancients: The Strange History of Tiger Nuts.” NPR, NPR, 27 Apr. 2016, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/04/27/472581773/loathed-by-farmers-loved-by-ancients-the-strange-history-of-tiger-nuts#:~:text=Matailong%20Du%2FNPR-,The%20earliest%20records%20of%20tiger%20nuts%20date%20back%20to%20ancient,Nutritionally%2C%20they%20do%20OK.

“Clove.” Edited by Melissa Petruzzello, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/plant/clove.

“Clove.” Medicinal Spices Exhibit – UCLA Biomedical Library: History & Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles, 2002, https://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?displayID=7.

“Coriander and Cilantro.” Coriander and Cilantro | Silk Routes, University of Iowa, https://iwp.uiowa.edu/silkroutes/coriander-and-cilantro.

Coriander, McGill University, 2007, https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/c/Coriander.htm.

“Coriander.” Coriander – an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/coriander#:~:text=Coriandrum%20sativum%2C%20colloquially%20known%20as,Bangladesh%20%5B17%E2%80%9320%5D.

F., Benzie Iris F, et al. “The Amazing and Mighty Ginger.” Herbal Medicine Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects, 2nd ed., Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, 2011.

Freedman, Paul H. Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. Yale University Press, 2009.

“Galangal.” Galangal – an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, Science Direct, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/galangal#:~:text=2%20Origin%20and%20distribution,from%20southern%20China%20and%20Java.

“Ginger.” Ginger | Silk Routes, University of Iowa, https://iwp.uiowa.edu/silkroutes/ginger.

“Greater Galangal.” Medicinal Spices Exhibit – UCLA Biomedical Library: History & Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles, 2002, https://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?displayID=29.

Hancock, James. Pepper. World History Encyclopedia, 2 Sept. 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/Pepper/.

Hancock, James. “The Early History of Clove, Nutmeg, & Mace.” World History Encyclopedia, 17 Oct. 2022, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1849/the-early-history-of-clove-nutmeg–mace/.

Hancock, James. “The Early History of Clove, Nutmeg, & Mace.” World History Encyclopedia, Https://Www.worldhistory.org#Organization, 17 Oct. 2022, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1849/the-early-history-of-clove-nutmeg–mace/.

“History of Pepper.” History of Pepper, International Pepper Community , https://www.ipcnet.org/history-of-pepper/.

History of Saffron, McGill University, 2007, https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/h/History_of_saffron.htm#:~:text=In%20ancient%20Persia%20saffron%20.

Jimenez-Brobeil, Sylvia A., et al. Introduction of Sugarcane in Al‐Andalus (Medieval Spain) and Its Impact … International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 16 May 2021, https://boris.unibe.ch/164037/1/Intl_J_of_Osteoarchaeology_-_2021_-_Jim_nez_u2010Brobeil_-_Introduction_of_sugarcane_in_Al_u2010Andalus_Medieval_Spain_and_its.pdf.

Kampen, Willem H. Sugarcane History. LSU AgCenter, 12 Oct. 2015, https://www.lsuagcenter.com/portals/communications/publications/agmag/archive/2002/fall/sugarcane-history.

“Long Pepper.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 16 Oct. 2018, https://www.atlasobscura.com/foods/long-pepper#:~:text=The%20long%20pepper%20hails%20from,wine%20hippocras%20until%20the%201500s.

“Long Pepper: A Forgotten Spice.” INDIAN CULTURE, Government of India, https://indianculture.gov.in/food-and-culture/spices-herbs/long-pepper-forgotten-spice.

Lyon, Stephanie. Cardamom, Small Cardamom, Green Cardamom. University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, 26 Oct. 2022, https://www.uwsp.edu/sbcb/cardamom-small-cardamom-green-cardamom/.

Mahr, Susan. “Cilantro / Coriander, Coriandrum Sativum.” Wisconsin Horticulture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/cilantro-coriander-coriandrum-sativum/.

McNamee, Gregory Lewis. “Cardamom.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 19 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/plant/cardamom.

Medicinal Spices Exhibit – UCLA Biomedical Library: History & Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles, 2002, https://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?displayID=15.

“Melegueta Pepper / Grains of Paradise.” Melegueta Pepper / Grains of Paradise | Silk Routes, University of Iowa, https://iwp.uiowa.edu/silkroutes/melegueta-pepper-grains-paradise.

“Peppercorn Guide.” Bon Appétit, Bon Appétit, 2 Feb. 2008, https://www.bonappetit.com/test-kitchen/ingredients/article/peppercorn-guide.Suriyagoda, Lalith, et al. “Ceylon Cinnamon”: Much More than Just a Spice – Wiley Online Library. New Phytologist Foundation, 8 Apr. 2021, https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ppp3.10192.